The Queen's English: Why does any British voter believe bigoted ‘Snobbery’?

Backed By Research & Data: Why does a 'posh' accent falsely associate with intelligence and how does it affect British Politics?

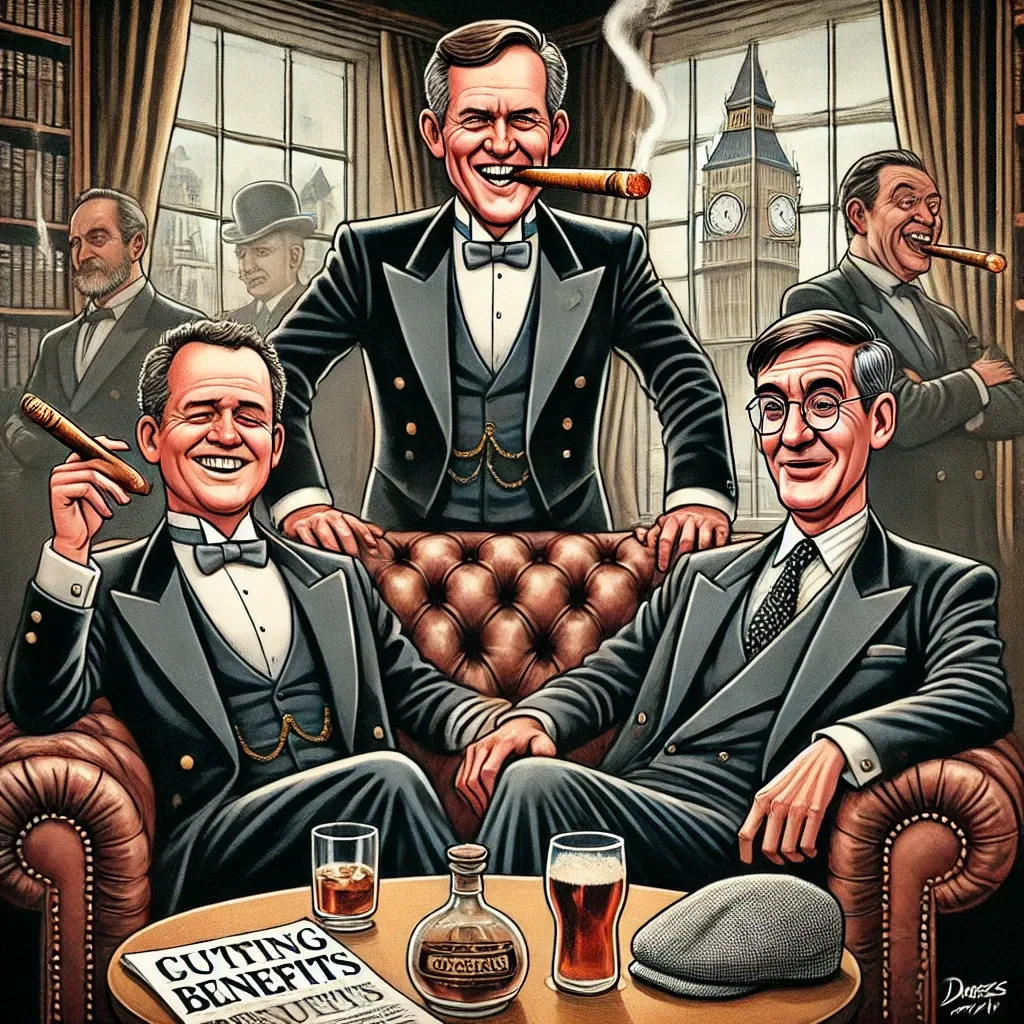

It’s no secret that the political class can be economical with the ‘truth’. Anecdotally, I have noticed a pattern of people (both in person and on social media) tending to believe more ‘well-spoken’ individuals, simply because “they sound like they know what they’re talking about”— even if what they are saying is baseless ugly bigotry dressed up as substantiative academia.

Therefore, I have taken the time to research and analyse if there is any truth in the claim that the public lend their faith to “posh voices”, and if so, are there is any psychological or institutional reasons for this? There are an overwhelming cluster of examples we will explore where an argument can be made that the political elite skew public perceptions through sociolinguistic means.

The Halo Effect and the Power of Perception

At the core of why the public might trust “posh voices” is a well-documented psychological bias called the Halo Effect. First articulated by Edward Thorndike (1920), the Halo Effect describes how an individual’s perception of one positive trait (like a refined accent or polished appearance) influences the perception of their overall competence (Thorndike, 1920). This cognitive bias helps explain why someone like Jacob Rees-Mogg, with his archaic vocabulary and Received Pronunciation (RP), is seen as more authoritative, even when his statements are demonstrably false or morally questionable.

For example, He infamously suggested that victims of the Grenfell Tower tragedy lacked “common sense” for not fleeing the blaze. Not only this, just a few weeks ago he appeared on Question time, stating that using a stick instead of the carrot approach to beat the poor was the only option for the nation to get back on it's feet– he received a round of applause from the audience. Despite the elitist and callous nature of these comments, his upper-class demeanor shielded him from conceding any political capital.

Jacob Rees-Mogg suggests that Grenfell victims lacked "common sense".

Oratory Bias in Britain: The Evidence

Being well spoken, and being able to articulate a point, is often related to training, and has nothing to do with accent. For example 53% of private schools offer the chance to join a debating society, compared to just 18% of state schools. However, the tone matters just as much as the delivery based on the following evidence:

- Multiple studies confirm that British society holds entrenched biases regarding accents. The Sutton Trust’s (2019) "Speaking Up" report found that 33% of professionals from working-class backgrounds felt their accents held them back in their careers. In contrast, those who spoke with RP were more likely to be perceived as competent and authoritative (Sutton Trust, 2019).

- Similarly, the Accent Bias in Britain study (2020) by Queen Mary University found that RP speakers were consistently rated as more trustworthy and intelligent, while regional accents like Scouse and Brummie were rated lower (Accent Bias in Britain, 2020). This reinforces why politicians who speak with RP are often more readily believed, regardless of the factual accuracy of their statements, harking back to the days where kneeling for the gentry was the norm.

- YouGov (2015) also revealed that 28% of Britons admit to judging a person’s intelligence based on their accent, with RP and Southern English accents receiving the highest ratings for competence (YouGov, 2015).

- Research by Lev-Ari and Keysar (2010) found that people are less likely to believe statements made by non-native speakers, indicating a psychological bias toward familiar, authoritative-sounding voices (Lev-Ari & Keysar, 2010). Additionally, Mahoney and Dixon (2002) demonstrated that in criminal cases, suspects with RP accents were judged as less guilty compared to those with regional accents (Mahoney & Dixon, 2002), proving a large societal inequality.

See William Hague's comments on Prescott's "English"

Institutional and Media Reinforcement

The media plays a significant role in perpetuating these biases. Figures like Douglas Murray, known for his ethno-nationalist rhetoric, frequently publish articles in The Spectator (edited by Andrew Neil) that frame divisive and xenophobic ideas in the language of reason and academia.

Highlighted by James O'Brien in How They Broke Britain, where he discusses figures like Neil and Murray and how they use linguistic sophistication to spout harmful rhetoric to mislead audiences, all while endorsing multiple Nazi sympathising organisations (O’Brien, 2023). He delves into Murray's Spectator articles and the constant berating of anything that isn't white, and how it dilutes British traditions, famous of course for confining British culture to Britain... providing you ignore a few centuries of history.

See Murray's work, which will always create Eurocentric discourse and exceptionalism

Harmful Psychological Impact

Giles and Coupland (1991) argue that by using RP or a “neutral” authoritative tone, right-wing media figures effectively shape public perception (Giles & Coupland, 1991). The language itself becomes a tool of persuasion, making bigotry sound reasonable. A key example is the Russian-Ukraine war, where Putin has outlined his perception of history which dictates that Ukraine is part of a "united Russia", using authoritative language to set the parameters of discourse, which encouraged much sympathy in the UK, particularly from Farage's Populist Far-Right enclaves.

During the Brexit campaign, the usual suspects played a crucial role in swaying public opinion on the Vote Leave campaign, with Johnson and cronies being funded by the Adam Smith society and other secret funders masquerading as think tanks. A discourse analysis of prominent Brexit-era articles shows that these figures often framed the debate around notions of sovereignty and national pride, rather than providing factual clarity about the issues we now face. This is because they hadn't a clue but managed to convince the public they did. As Foucault (1972) noted, “language doesn’t describe reality; it creates it” (Foucault, 1972, p.49).

Conclusion

The British public’s trust in "The Queens English" voices is deeply rooted in psychological biases, institutional reinforcement, and media complicity. If we are to combat this, we must recognise that an authoritative voice does not necessarily convey truth. Instead, we must look beyond accents and rhetorical flourishes to the actual evidence underpinning public discourse.

I’m also not totally disregarding the art of oratory delivery; it is essential that public speaking is built into working class educational institutions, allowing them to feel more comfortable in political discussions.

Of course, not many people know how to do that; I have written an article which provides the tools for reliable information for you to make your own mind up about politics!

Sources used in this Article

- Thorndike, E.L. (1920). A constant error in psychological ratings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 4(1), pp.25–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0071663

- Giles, H. and Coupland, N. (1991). Language: Contexts and Consequences. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

- Bishop, H., Coupland, N. and Garrett, P. (2005). Conceptual accent evaluation: Thirty years of accent prejudice in the UK. Acta Linguistica Hafniensia, 37(1), pp.131–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/03740463.2005.10416087

- Lev-Ari, S. and Keysar, B. (2010). Why don't we believe non-native speakers? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(6), pp.1093–1096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2010.05.025

- Mahoney, B. and Dixon, J.A. (2002). The effect of accent evaluation and evidence on a suspect's perceived guilt and criminality. The Journal of Social Psychology, 142(5), pp.587–600. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224540209603923

- Cialdini, R.B. (1984). Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion. New York: HarperCollins.

- Sutton Trust. (2019). Speaking Up: Accents and Social Mobility. https://www.suttontrust.com/our-research/speaking-up/

- Accent Bias in Britain. (2020). https://accentbiasbritain.org

- YouGov. (2015). Most and least trusted accents. https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/articles-reports/2015/02/18/most-and-least-trusted-accents

- O’Brien, J. (2023). How They Broke Britain. London: WH Allen.

- Foucault, M. (1972). The Archaeology of Knowledge. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Mutlu, C. E., & Salter, M. B. (2013). Research Methods in Critical Security Studies: An Introduction. New York: Routledge.

- Queen Mary University of London. (2019). British people still think some accents are smarter than others. Retrieved from https://www.qmul.ac.uk/media/news/2019/hss/british-people-still-think-some-accents-are-smarter-than-others–what-that-means-in-the-workplace.html

- Sutton Trust. (2022). Accents and Social Mobility. Retrieved from https://www.suttontrust.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Accents-and-social-mobility.pdf

- The Open University. (2019). The impact of British accents on perceptions of eyewitness statements. Retrieved from https://oro.open.ac.uk/66672/10/The%20impact%20of%20British%20accents%20on%20perceptions%20of%20eyewitness%20statements.pdf

- Byline Times. (2024). Hate Sells: ‘The Spectator Cannot Defend Douglas Murray But It Won’t Sack Him’. Retrieved from https://bylinetimes.com/2024/08/19/hate-sells-the-spectator-cannot-defend-douglas-murray-but-it-wont-sack-him/

- The Guardian. (2021). Trump’s British cheerleaders are rushing to denounce him. It’s too little, too late. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/jan/12/trump-british-cheerleaders-rightwing-figures

- Medium. (2023). The power and prejudices of received pronunciation. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@emmaclarke/the-power-and-prejudices-of-received-pronunciation-b07112e456c7