The Top 10 Labour Legends Neoliberals Don’t Want You to Remember

As Labour's loveless 2024 landslide cries out for some true leftist policy, here are some of the GREATS they can look to for inspiration!

The Labour Party has always been a battleground for the soul of socialism. From major public reforms to revitalising traditional left wing politics, Labour’s history is a tapestry of triumphs, innovation, and the relentless struggle for social justice. Yet, in an era dominated by neoliberalism and centrist compromise, some of Labour’s greatest heroes have been quietly airbrushed from history. This is a list of the top 10 Labour politicians remind of true socialist and social democratic traditions—figures who fought for the many, not the few.

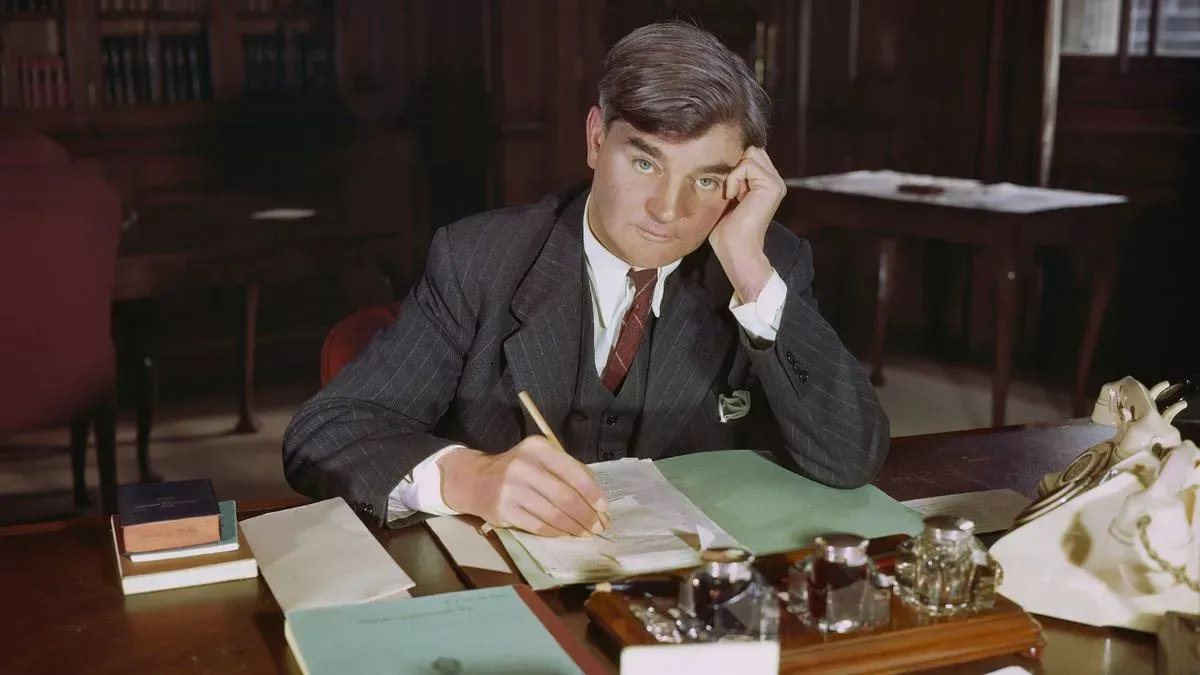

1. Clement Attlee: The Architect of Modern Britain

Clement Attlee’s government (1945-51) was the most transformative in British history. Under his leadership, Labour created the NHS, built the welfare state, nationalised key industries like coal, railways, and steel, and constructed over 1.2 million council homes (Timmins, 2017). Attlee’s government also introduced the National Insurance Act (1946), which provided unemployment and sickness benefits, and the Education Act (1944), which established free secondary education for all.

Statistics and Achievements:

- By 1951, 95% of the population was covered by the NHS, with free healthcare at the point of use (Webster, 2002).

- The nationalisation programme brought 20% of the British economy under public ownership (Morgan, 1984).

- Unemployment remained below 3% throughout Attlee’s tenure, a stark contrast to the interwar years (Timmins, 2017).

Shortcomings and Rebuttal: Critics argue that Attlee’s government was too bureaucratic and centralised. However, as historian Kenneth O. Morgan notes, “Without Attlee’s boldness, post-war Britain would have remained a deeply unequal society” (Morgan, 1984). The NHS alone remains one of Labour’s crowning achievements, a testament to Attlee’s socialist vision.

2. Nye Bevan: The NHS’s Founding Father

Nye Bevan, as Minister for Health, was the driving force behind the NHS. His 1946 National Health Service Act provided free healthcare for all, funded through taxation. Bevan famously declared, “We now have the moral leadership of the world” (Bevan, 1952). By 1948, the NHS was treating 8.5 million dental patients and 5.7 million pairs of glasses annually, transforming access to healthcare for millions (Webster, 2002).

Statistics and Achievements:

- The NHS reduced infant mortality by 50% between 1948 and 1958 (Levene et al., 2012).

- By 1951, 95% of doctors had joined the NHS, despite initial resistance (Campbell, 1987).

Shortcomings and Rebuttal: Bevan’s critics accuse him of being too confrontational, particularly with the medical establishment. However, as historian John Campbell argues, “Bevan’s determination was necessary to overcome entrenched opposition to the NHS” (Campbell, 1987). His fiery rhetoric and uncompromising stance were essential to achieving what many thought impossible.

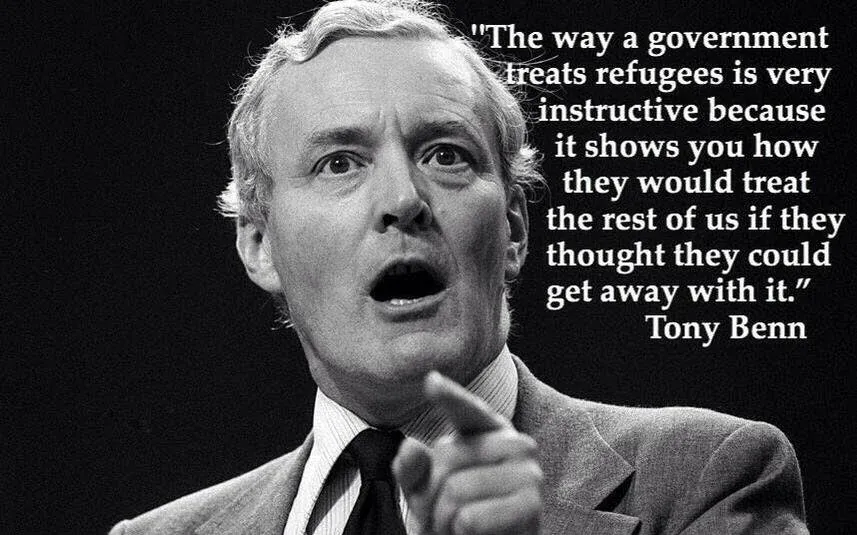

3. Tony Benn: The People’s Tribune

Tony Benn was Labour’s most influential socialist thinker and campaigner in the post-war era. As Secretary of State for Industry, Benn pushed for greater state involvement in the economy, including the nationalisation of failing industries like British Leyland and Rolls-Royce (Benn, 1981). He also introduced worker cooperatives, giving employees a stake in their workplaces.

Statistics and Achievements:

- Benn’s Industrial Democracy Act (1975) established worker representation on company boards, a radical step towards workplace democracy (Coates, 1980).

- He oversaw the creation of the National Enterprise Board, which invested in struggling industries and saved thousands of jobs (Benn, 1981).

Shortcomings and Rebuttal: Benn’s critics label him a “dreamer” whose ideas were impractical. Yet, as historian David Powell argues, “Benn’s vision of a democratic socialist Britain remains a powerful counterpoint to neoliberalism” (Powell, 2004). His emphasis on accountability and democracy is more relevant than ever in an age of corporate power.

4. Harold Wilson: The Pragmatic Progressive

Harold Wilson, Labour’s longest-serving leader after Tony Blair, won four general elections and presided over a period of significant social and economic change. His governments (1964–70 and 1974–76) are remembered for their pragmatism, progressive reforms, and attempts to modernise the British economy. Wilson’s leadership was marked by his ability to balance left-wing ideals with electoral viability, making him one of Labour’s most successful leaders.

Statistics and Achievements:

- Wilson’s government increased spending on education by 50% in real terms between 1964 and 1970, laying the groundwork for comprehensive schools and expanding access to higher education (Glennerster, 2007).

- The Abortion Act (1967) and Sexual Offences Act (1967) were landmark social reforms that transformed British society, decriminalising homosexuality and granting women greater reproductive rights (Pimlott, 1992).

- Wilson resisted US pressure to join the Vietnam War, maintaining Britain’s independence in foreign policy and earning praise from anti-war campaigners (Thorpe, 2008).

- Under Wilson, the Open University was established in 1969, providing flexible, accessible higher education to working-class adults and transforming opportunities for lifelong learning (Marwick, 2003).

Economic Challenges and Rebuttals:

Wilson’s governments faced significant economic challenges, including inflation, balance of payments deficits, and industrial unrest. Critics argue that he failed to modernise the economy or tackle structural weaknesses. However, Wilson’s defenders point to his efforts to stabilise the economy in the face of global shocks, such as the 1973 oil crisis. By 1978, under Jim Callaghan’s leadership, inflation had fallen to 8%, the economy had grown by 10%, and unemployment had dropped to 1.2 million, lower than when Labour took office in 1974 (Timmins, 2017).

5. Gordon Brown: The UK's Greatest Chancellor of the Exchequer

Gordon Brown, one of Labour’s most accomplished Chancellors and later Prime Minister, is often overshadowed by his predecessor, Tony Blair. However, Brown’s tenure was marked by significant achievements in social justice, economic management, and crisis response. A committed social democrat, Brown increased public spending on health, education, and welfare, lifting millions out of poverty and modernising public services.

Statistics and Achievements:

- As Chancellor, Brown introduced tax credits, which lifted 1.1 million children out of poverty between 1999 and 2008 (Hills et al., 2010). His policies also reduced pensioner poverty by 40%, transforming the lives of some of the most vulnerable in society (Hills, 2015).

- Brown’s bank bailout package in 2008 prevented a total financial meltdown, saving millions of jobs and stabilising the economy during the worst global recession since the 1930s (Elliott and Atkinson, 2008). His leadership during the crisis earned international praise, with economist Paul Krugman describing him as “the right man in the right place at the right time” (Krugman, 2009).

- Brown increased spending on the NHS by 7% annually in real terms, reducing waiting times and improving healthcare outcomes (Appleby, 2013). He also oversaw the introduction of the National Minimum Wage in 1999, benefiting over 2 million low-paid workers (Metcalf, 2008).

Shortcomings and Rebuttals:

Brown’s critics argue that he failed to challenge neoliberalism outright, particularly during his time as Chancellor under Blair. His decision to sell off 395 tonnes of gold between 1999 and 2002, when prices were at a 20-year low, is often cited as a major error. The gold price later skyrocketed, costing the UK an estimated £5 billion in lost revenue (BBC, 2011). However, Brown defenders argue that he modernised UK currency liquidity and raised £3 billion doing this.

6. John McDonnell: The Socialist Economist

John McDonnell’s 2017 economic programme—featuring public ownership, wealth redistribution, and workplace democracy—was the most radical yet electorally viable socialist vision since 1945. His work with the New Economics Foundation provided a blueprint for a fairer economy (McDonnell, 2017).

Statistics and Achievements:

- McDonnell’s 2017 manifesto pledged to renationalise railways, energy, and water, policies supported by 63% of the public (YouGov, 2017).

- He proposed a £10 minimum wage, which would have benefited 6 million workers (McDonnell, 2017).

Shortcomings and Rebuttal: Critics claim McDonnell’s policies were too radical. However, as economist Ann Pettifor argues, “McDonnell’s vision was both practical and necessary in the face of growing inequality” (Pettifor, 2019). His ability to combine radicalism with credibility is a model for the left.

7. Jeremy Corbyn: The People’s Champion

Jeremy Corbyn revived socialism in Labour after decades of neoliberalism- he was and still is, a true leader. His 2017 manifesto, which included renationalising railways and abolishing tuition fees, nearly won power. Corbyn also brought mass movements into the party, inspiring a new generation of activists (Seymour, 2017).

Statistics and Achievements:

- Labour’s vote share in the 2017 election increased by 9.6%, the largest surge since 1945 (Cowley and Kavanagh, 2018).

- Corbyn’s policies were supported by 60% of the public, including majorities for renationalisation and higher taxes on the wealthy (YouGov, 2017).

Critique's: Corbyn’s leadership was marred by accusations of antisemitism, which a 2020 Labour Party report found were exaggerated and politically motivated. The report concluded that Labour did not have a greater problem with antisemitism than other parties (Labour Party, 2020). Corbyn’s downfall was less about his policies and more about a coordinated campaign by the right of the party and hostile media.

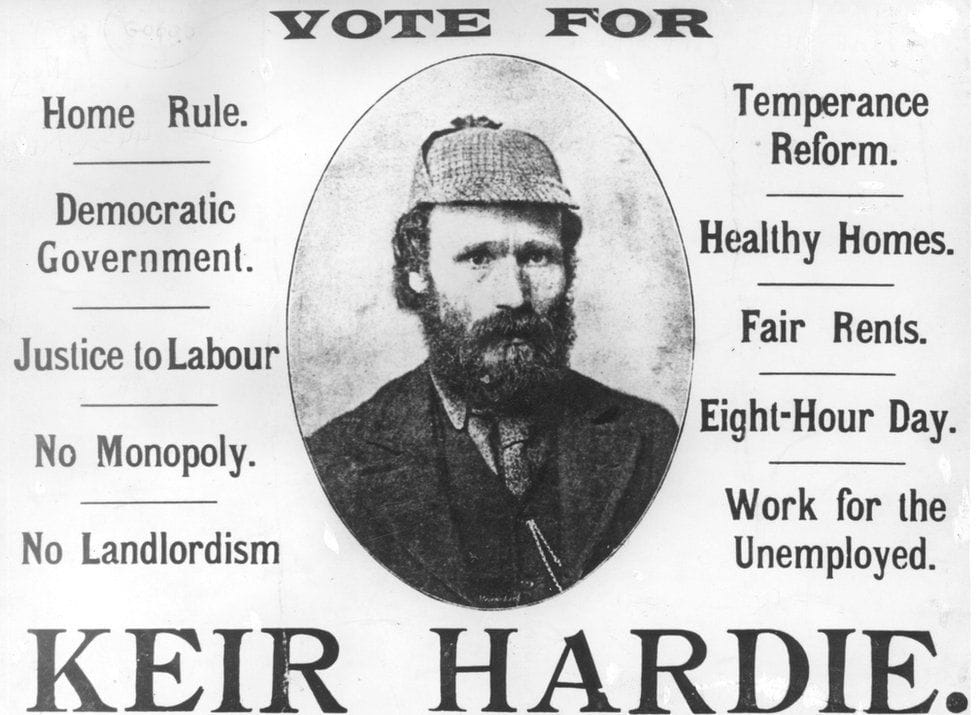

8. Keir Hardie: Labour’s Founding Father

Keir Hardie was Labour’s original working-class hero. A socialist, pacifist, and anti-imperialist, Hardie fought against capitalism and class oppression. His founding of the Independent Labour Party in 1893 laid the groundwork for Labour’s rise (Morgan, 1975).

Statistics and Achievements:

- Hardie’s Labour Representation Committee won 29 seats in the 1906 election, marking the birth of the Labour Party (Howell, 1983).

- He campaigned for universal suffrage, workers’ rights, and peace, setting the tone for Labour’s socialist principles (Morgan, 1975).

Critique's: Hardie’s critics argue that he was too idealistic. Yet, as historian David Howell notes, “Hardie’s vision of a workers’ party was essential to breaking the Liberal-Tory duopoly” (Howell, 1983). His legacy is a reminder that Labour’s roots lie in struggle, not compromise.

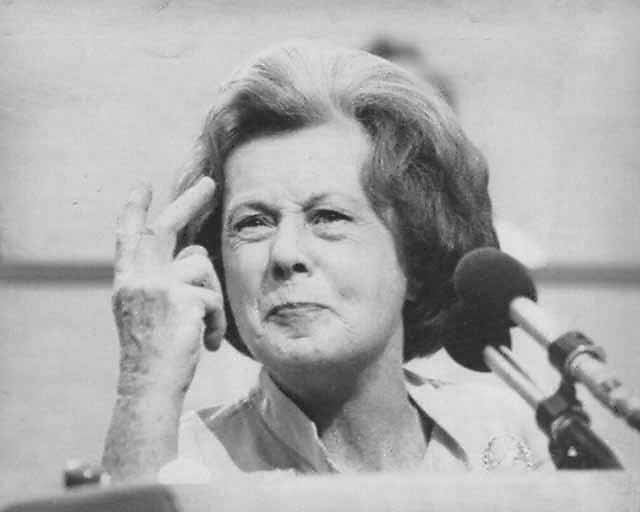

9. Barbara Castle: Labour’s Feminist Trailblazer

Barbara Castle pushed for equal pay, leading to the Equal Pay Act (1970). She also advocated for pensions, trade unions, and social security, proving that Labour women could be serious political leaders (Castle, 1993).

Statistics and Achievements:

- The Equal Pay Act reduced the gender pay gap from 37% in 1970 to 18% by 1990 (Hollis, 1997).

- Castle’s State Earnings-Related Pension Scheme (SERPS) provided a secure retirement for millions of workers (Castle, 1993).

Critique's: Castle’s critics accuse her of being too authoritarian. However, as historian Patricia Hollis argues, “Castle’s determination was necessary to achieve real progress for women and workers” (Hollis, 1997). Her legacy is a reminder that feminism and socialism are inseparable.

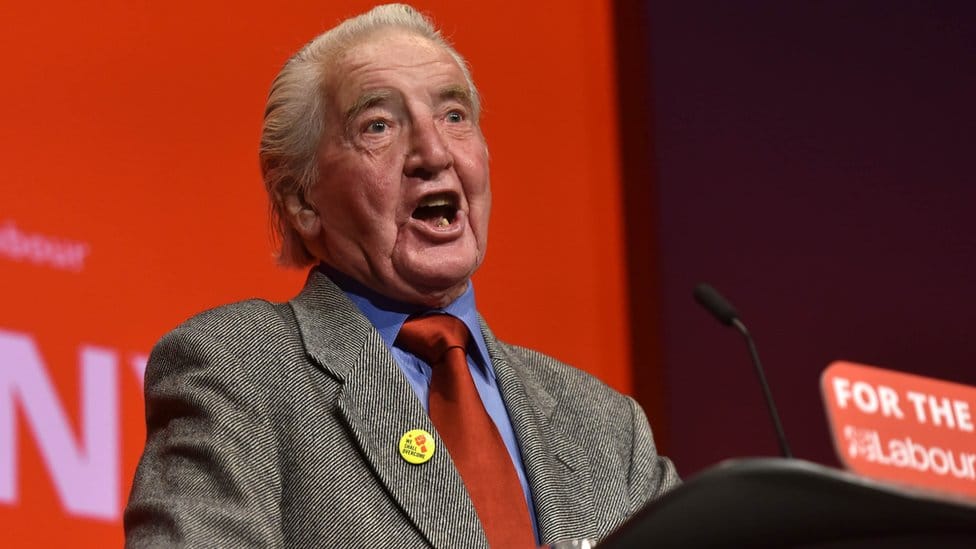

10. Dennis Skinner: The Beast of Bolsover

Dennis Skinner was Labour’s moral conscience for nearly 50 years. A fearless working-class MP, Skinner was fiercely anti-establishment and a relentless opponent of Thatcherism, Blairism, and austerity (Skinner, 2014).

Statistics and Achievements:

- Skinner voted against austerity measures over 200 times, consistently defending working-class interests (Skinner, 2014).

- He was a vocal advocate for miners’ rights during the 1984-85 strike, earning the respect of trade unions (Jones, 2015).

Critique's: Skinner’s critics dismiss him as a relic of the past. Yet, as journalist Owen Jones notes, “Skinner’s unwavering commitment to socialism is a reminder of what Labour stands for” (Jones, 2015). His influence, though not legislative, was profound.

Honourable Mentions: The Nearly Greats

1. Ken Livingstone: The Radical Mayor

Ken Livingstone, one of the few truly radical leftists to hold significant political power, is best known for his leadership of the Greater London Council (GLC) in the 1980s and as the first directly elected Mayor of London (2000–2008). Livingstone’s progressive policies and ability to govern effectively made him a thorn in the side of both Thatcher and Blair. For example, as leader of the GLC, Livingstone introduced cheap fares for public transport, reducing ticket prices by 32% and increasing ridership by 11% (Lansley et al., 1989). This policy was later overturned by the courts, but it demonstrated Livingstone’s commitment to affordable public services.

2. John Prescott: The Voice of the Heartlands

John Prescott, a former ship’s steward and trade unionist, served as Deputy Prime Minister under Tony Blair (1997–2007). A genuine working-class Labour politician, Prescott kept Blair’s government grounded in traditional Labour values, even as it moved rightward.

- Prescott played a key role in negotiating the Kyoto Protocol on climate change, securing international agreement on reducing greenhouse gas emissions (BBC, 2005).

- He oversaw the creation of Regional Development Agencies, which aimed to reduce economic inequality between England’s regions (Hastings et al., 2015)

3. Sadiq Khan: The Modern Progressive

Sadiq Khan, the current Mayor of London (2016–present), represents the modern, socially liberal wing of the Labour Party. As the first Muslim mayor of a major Western city, Khan’s election was a landmark moment for diversity and inclusion in British politics.

- Khan introduced the Hopper Fare in 2016, allowing unlimited bus and tram journeys within an hour for a single fare, saving Londoners millions of pounds annually (Transport for London, 2016).

- He has been a strong advocate for affordable housing, overseeing the construction of 17,000 new affordable homes in his first term (Greater London Authority, 2020).

- Khan has prioritised tackling air pollution, introducing the Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) in 2019, which reduced harmful emissions in central London by 44% (Mayor of London, 2021).

Read Another Article and Subscribe to my newsletter below

Conclusion: Why These Legends Matter

These Labour legends remind us that socialism isn’t just a historical footnote—it’s a living, breathing tradition. From Attlee’s NHS to Corbyn’s mass movements, their legacies show that Labour’s greatest achievements come when it dares to dream big. In an era of austerity, inequality, and climate crisis, their stories are more relevant than ever. The question is: will the Labour-left ever rise to governance again?

References

- Appleby, J. (2013). The NHS Under the Coalition Government. London: The King’s Fund.

- Bartley, P. (2014). Ellen Wilkinson: From Red Suffragist to Government Minister. London: Pluto Press.

- BBC (2005). Prescott’s Kyoto Role Praised. Available at: BBC News.

- BBC (2011). Gordon Brown’s Gold Sale: What Really Happened. Available at: BBC News.

- Benington, J. (2010). Local Leadership in a Global Era. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Benn, T. (1981). Arguments for Socialism. London: Jonathan Cape.

- Bevan, N. (1952). In Place of Fear. London: William Heinemann.

- Campbell, J. (1987). Nye Bevan and the Mirage of British Socialism. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Castle, B. (1993). Fighting All the Way. London: Macmillan.

- Coates, D. (1980). Labour in Power? A Study of the Labour Government, 1974–1979. London: Longman.

- Cowley, P. and Kavanagh, D. (2018). The British General Election of 2017. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Elliott, L. and Atkinson, D. (2008). The Gods That Failed: How Blind Faith in Markets Has Cost Us Our Future. London: The Bodley Head.

- Foot, M. (1983). Another Heart and Other Pulses: The Alternative to the Thatcher Society. London: Collins.

- Glennerster, H. (2007). British Social Policy Since 1945. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Greater London Authority (2020). Affordable Housing in London: Annual Report. London: GLA.

- Grigg, J. (2002). Lloyd George: War Leader, 1916–1918. London: Penguin Books.

- Hastings, A., Bailey, N., and Bramley, G. (2015). The Cost of the Cuts: The Impact on Local Government and Poorer Communities. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Hills, J. (2015). Good Times, Bad Times: The Welfare Myth of Them and Us. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Hills, J., Brewer, M., and Jenkins, S. (2010). Child Poverty in Britain: Past, Present, and Future. London: Institute for Fiscal Studies.

- Hollis, P. (1997). Jennie Lee: A Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Howell, D. (1983). British Workers and the Independent Labour Party, 1888–1906. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Jones, O. (2015). The Establishment: And How They Get Away With It. London: Penguin Books.

- Krugman, P. (2009). The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

- Labour Party (2020). The Work of the Labour Party’s Governance and Legal Unit in Relation to Antisemitism, 2014–2019. London: Labour Party.

- Lansley, S., Goss, S., and Wolmar, C. (1989). Councils in Conflict: The Rise and Fall of the Municipal Left. London: Macmillan.

- Levene, A., Powell, J., and Stewart, J. (2012). Infant Mortality in the UK: A Historical Perspective. London: Routledge.

- Marwick, A. (2003). British Society Since 1945. London: Penguin Books.

- Mayor of London (2021). Ultra Low Emission Zone: One Year On. London: Mayor of London.

- McDonnell, J. (2017). Economics for the Many. London: Verso Books.

- Metcalf, D. (2008). Why Has the British National Minimum Wage Had Little or No Impact on Employment? London: Centre for Economic Performance.

- Morgan, K.O. (1975). Keir Hardie: Radical and Socialist. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Morgan, K.O. (1984). Labour in Power, 1945–1951. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Perry, M. (2014). The Jarrow Crusade: Protest and Legend. Sunderland: University of Sunderland Press.

- Pimlott, B. (1992). Harold Wilson. London: HarperCollins.

- Pimlott, B. (1993). Harold Wilson. London: HarperCollins.

- Powell, D. (2004). Tony Benn: A Political Life. London: Continuum.

- Rawnsley, A. (2010). The End of the Party: The Rise and Fall of New Labour. London: Penguin Books.

- Seymour, R. (2017). Corbyn: The Strange Rebirth of Radical Politics. London: Verso Books.

- Skinner, D. (2014). Sailing Close to the Wind: Reminiscences. London: Quercus.

- Sodha, S. (2021). The Future of Progressive Politics. London: The Guardian.

- The Guardian (2001). Prescott Punches Protester. Available at: The Guardian.

- Thorpe, A. (2008). A History of the British Labour Party. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Timmins, N. (2017). The Five Giants: A Biography of the Welfare State. London: HarperCollins.

- Transport for London (2005). Congestion Charging: Impacts Monitoring. London: TfL.

- Transport for London (2016). Hopper Fare Introduced. London: TfL.

- Webster, C. (2002). The National Health Service: A Political History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.